Whenever we talk about shark conservation, we often mention how sharks are important to maintain the balance of the marine ecosystem and that they’re threatened by fisheries and the loss of suitable habitat offering ample resources and a safe place to reproduce. This is basic information that everybody should learn. But I realize that not everybody is familiar with a lot of the additional terms and abbreviations we use, and therefore I listed ten common terms in order for you to better understand the principles of shark conservation.

1. CARTILAGINOUS

Shark and the closely related skates and rays are cartilaginous fish, which means their entire skeleton is made up of cartilage, instead of bones like other fish and mammals. Their extended evolutionary history that dates back millions of years has made sharks physiologically very different from other fish. For instance, they have different scales, they regulate buoyancy in the water with their liver instead of a swim bladder, and they reproduce differently. Because of the inherent biological differences, sharks and rays should be considered separate from other fish in conservation and management.

2. REPRODUCTION

In general, sharks reproduce slowly. It can take years before the young are ready to mate, their gestation takes months, and they only get a few young per year. Their speed of reproduction is even more comparable to large mammals than to other fish. Different shark species have different reproductive modes. Some sharks and most rays are egg-laying. But many shark species are live bearing, giving birth to miniature versions of themselves that have to be self-sufficient from the moment of birth.

3. OVERFISHING

The term overfishing refers to a state in which a population of fish is exploited at a faster rate than it can replenish itself. So fish that reproduce extremely slowly, as sharks do, are particularly vulnerable to overfishing.

4. BYCATCH

Sharks are often caught as bycatch in fisheries targeting other species. Unintentionally caught sharks are often thrown back into the sea, but this does not guarantee their survival. Because of the insufficient data on the amount of sharks that are caught and discarded, the estimated mortality rates of sharks are usually a gross underestimation.

5. FINNING

Shark fins are a delicacy in the Asian market, where they are used for shark fin soup, among other things. Shark finning is the process of removing the shark’s fins at sea, after which the remains of the shark is often thrown back overboard. The removal of a shark’s fins on land is not called finning, because the shark was landed with all its fins attached. Numerous countries already banned shark finning, but many more are yet to follow.

6. EEZ

The Exclusive Economic Zone is the water that extends 200 sea miles from the coast over which a country has its own say with regard to fisheries and natural legislation. Within an EEZ, the national government can thus decide whether, and on what terms shark fishing is allowed. Outside of the 200 sea mile limit, the sea becomes international water where rules apply that are imposed by international law.

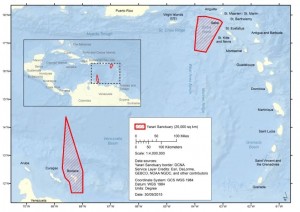

7. Shark reserves

More and more places around the world have started to establish Shark Sanctuaries: reserves where no shark fishing is allowed, and where they actively work towards improving the quality of the shark’s habitat, for instance by the prohibition of certain human activities. In the Dutch Caribbean, the Yarari reserve is an example of a shark reserve. Earlier I spoke about the importance of shark sanctuaries.

8. BRUV

Because we can not always see underwater, which makes it hard to figure out what swims around there, researchers install cameras on the bottom with bait in front of it to attract fish, called Baited Remote Underwater Videos (BRUVs). After leaving these out for several days they can deduce from the footage what species occur in the area. Other ways of determining species occurrence are through catch data from commercial fisheries and independent fishing expeditions.

9. TAGGING

Sharks are tagged to assess where sharks are swimming and for what purposes they stay in certain places. This usually happens by catching the animal and placing a tag, or transmitter on the dorsal fin, or with a small incision in the abdominal cavity. Different tags and transmitters give different data, such as location, depth, temperature, swimming speed, and motion.

10. IUCN SSG

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is concerned with the categorization of nature’s threat of extinction. Within the IUCN there is a Shark Specialist Group (SSG) that consists of a team of the world’s leading experts, who have the task to assess the status of all shark species. The different statuses that can be appointed to a species are Data Deficient, Least Concern, Vulnerable, Near Threatened, Endangered, Critically Endangered, and (Locally) Extinct. You can find the different criteria for these statuses on the IUCN Red List website.

By Linda Planthof